Foresight Africa: The Takeaways of the 2020 AIEC Conference

- 07

- Dec

AIEC 7th Edition of the African Entrepreneurs Conference

On 26th and 27th November, AIEC supported by its partners brought together professionals for the 7th edition of the African Entrepreneurs Conference, an action-packed two-day event. “Unlocking Africa’s Hidden Potential” from an entrepreneurial perspective was the central theme of this year’s conference. In line with Covid-19 regulations, the conference took place online and the programme committee delivered an extraordinary event on transforming the economic narrative of Africa. AIEC pulled together a list of exceptional speakers who shared their distinctive expertise in global leadership, technocracy, academia, and business to discuss entrepreneurial-related topics for Africa’s future investment solutions. All this was aimed at supporting inclusive and sustainable economic growth and setting up employment opportunities. The goal was to create an environment and a dynamic in which informative dialogues could support Africa-based enterprises to engage with international businesspeople and attract up to USD15 bn of investments.

This blog shares the three main takeaways from the insight-rich two-day events.

- Intra-Africa Trade Deserves the Same Recognition as International Trade.

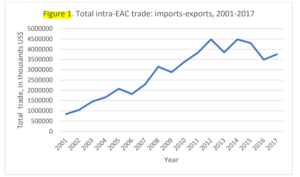

For the purpose of simplicity, this blog focuses on the case of the regional economic community (REC) in East Africa, the EAC connecting Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and South Sudan. Thonke and Spliid found that despite being the second most integrated African REC if compared to intra-regional trade levels of the European Union, the EAC underperforms (Thonke and Spliid, 2012). On an optimistic note, recent years have shown a positive growth trend in intra-EAC trade levels (see Figure 1).

However, discrepancies exist between the rhetoric outlined in free-trade area agreements and the reality of its implementation. To complicate things, non-tariff barriers (NTBs) in the form of transit costs, especially for landlocked states like Uganda, either make it difficult to transport goods to ports for export or where it is cheaper to export raw materials for transformation overseas rather than to partner states of the same REC (Moseley, 2016). Importantly, it is in the interest of policymakers that more attention is paid to recognising the inhibitive role of NTBs, especially for smallholder farmers. This is because were engaging in global value chains is out of reach financially for smallholders, regional value chains present more affordable market opportunities where barriers to entry are less stringent. In short, intra-Africa trade stimulates investing in African capabilities and development occurring within the continent as well as for the continent.

This aspect of the intra-Africa trade was greatly highlighted with the presentation about the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). AfCFTA is fixed in Agenda 2063 and it will be the greatest free trade area in the world only compare to the creation of the World Trade Organization in 1994. It has been signed by 54 member states out of the 55 in the African Union. Its main aim is to “create a single continental market for goods and services with free movement of people and investments”. As such it will help to increase free trade-in and across African thereby increasing competitiveness and supporting the economic transformation in Africa.

According to the EU-AU partnership, AfCFTA intra-Africa trade is expected to increase from about 13% to 25% or even more with better harmonisation and coordination of trade liberalisation. This will be made even better by a “complementary Single African Air Transport Market and the Protocol on Free Movement of Persons”. Also, AfCFTA is designed through the lens of women and youth that are producing goods and services in Africa so that they too can have a place in the free trade market. It is expected to be launched on 1 January 2021. (Africa-EU Partnership,2020)

2. Technology-based Tools are Enablers for Improving Africa’s Business Landscape.

It is well renowned that technology-based tools will support Africa to fast-track the current slow pace of structural change for a speedy Fourth Industrial Revolution. A topic that has been previously expanded on in our blog specific to the agriculture sector.

From an entrepreneurial perspective, private businesses in Africa recognise the impact digital changes have on their operations. A report survey carried out by PwC Consultancy in 2019 reveals that 81% of private business leaders in Africa have positive attitudes towards digitalising business practices (i.e., The Internet of Things, blockchain, and augmented reality) viewing these as ‘highly relevant’ to their future operations (PwC, 2019).

Blockchain used in insurance, banking, and travel

The problem is that applying these digital tools to the business landscape in Africa presents greater challenges compared to their counterparts in Europe, because of less developed digital infrastructure (in terms of reliable broadband coverage), unstable financial systems, and inadequate technological skills. The PwC report paints an incredibly optimistic picture of business leaders’ willingness to adopt new technologies which often is the very bottleneck in the first place. Where optimism is the driving force that leads to positive progress, the fact that the information regarding the respondents of the survey is unavailable to the public is problematic. It would therefore be interesting to gain an insight into the profiles of the business leaders and how they were sampled.

In the end, conference participants called for action by their governments to enhance implementation of existing policies to develop digitalisation, and expand them also, by boosting education and infrastructure and thereby accelerate the adoption of digital solutions in all sectors and territories – agriculture in rural areas in particular.

3. Creating an Inclusive Business Environment for Women Entrepreneurs to Thrive

Woman entrepreneurship in Africa

Against the misconception about gender-lens investing, the Sub-Saharan African region is standalone where there are more women taking on a career in entrepreneurship compared to men. Despite this positive fact, it is tougher for women-owned businesses to secure financing in terms of bank loans, angel investment, and venture capital than their male counterparts. For example, investors of venture capital have disregarded female entrepreneurs because of the industry’s focus on tech companies that are for the most part male-owned. Tech companies have not attracted businesswomen, although this seems to be slowly shifting (Phiri, 2020). In this context, partnering with the business private sector to leverage synergies for enterprise development should be fundamental to create lucrative opportunities for Africa’s women entrepreneurs (Rouanet and Delavelle, 2020). Government leaders of Africa are beginning to acknowledge women’s role as forces for growth. Targeting interventions as well as advancing the culture of gender equality aligns with the narrative of smart economics, sound business practice, and inclusive development policy.

AIEC together with its partners is set to make its contribution to a revolution in the business landscape of Africa by strengthening the capabilities of the entrepreneurs in its network. At EuroAfri Link, we are proud to have been a part of the planning and execution of the AIEC Conference and we look forward to continuing our strong cooperation with the AIEC on this exciting annual project.

References

Africa-EU Partnership. (2020). African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) [Online]. Available from https://africa-eu-partnership.org/en/afcfta

International Trade Centre (ITC). (2019). Trade Map database. [Online]. Available from https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx.

Marr, B. (2020). ‘Fascinating Examples of How Blockchain Is Used in Insurance, Banking and Travel’. Forbes. [Online]. Available from https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2020/08/05/fascinating-examples-of-how-blockchain-is-used-in-insurance-banking-and-travel/?sh=4c13f2b54b3d.

Mlambo, I. (2019). ‘Woman entrepreneurship in Africa’. Fokused Woman. [Online]. Available from https://fokusedwoman.wordpress.com/2019/02/08/woman-entrepreneurship-in-africa-2/.

Moseley, W. (2016). ‘Regional Value Chains and Productivity Enhancement in Africa’. In Contemporary Regional Development in Africa, (ed.). Hanson, K. Abingdon: Routledge.

PwC. (2019). Africa Private Business Survey 2019. [Online]. Available from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/entrepreneurial-and-private-companies/emea-private-business-survey/pwc-emea-private-business-africa-report-2019.pdf.

Phiri, L. (2020). ‘Investing in women entrepreneurs in Africa’. Africa Global Funds. [Online]. Available from https://www.africaglobalfunds.com/analysis/analysis-and-strategy/investing-in-women-entrepreneurs-in-africa/.

Rouanet, L. and Delavelle, F. (2020). ‘Female Entrepreneurship, Key Ingredient for Africa’s Growth’. Ideas4Development. [Online]. Available from https://ideas4development.org/en/ffemale-entrepreneurship-key-ingredient-africa-growth/.

Thonke, O. and Spliid, A. (2012). ‘What to expect from regional integration in Africa’. African Security Review. 21(1), 42-66.

By EAL, Eukalypton and AIEC